Why (not) to cut? Making sense of the current policy debate

Proponents and opponents of cutting policy rates are asking different questions. The disagreement can be boiled down to different view on neutral rate, and is mirror image of last decade.

For approximately last six months the debate between proponents and opponents of monetary easing has been stuck in a place where both sides seem to be talking past each other (not an unusual occurrence in public debate, for sure). The proponents of easing immediately are pointing out that inflation has moderated a lot and is not far form target, while labour market has softened, so there is no reason to keep rates elevated. The opponents are saying that there is no reason to lower rates, given that inflation is still above target and (discounting last two months in U.S.) it does not show any clear tendency to decrease, while labour market is far from soft.

In other words, the two camps are asking two different questions, reflecting different views on what is the “default” action. The proponents of easing are asking “Why should we keep interest rates this high?”, and opponents are asking “Why should we lower rates?”. Both questions are valid questions, of course. The problem is that each camp is refusing to answer the question of the other camp, so that we are really not moving forward in the discussion.

If only we would know the neutral rate

Interestingly, one can really translate this debate into debate about the neutral interest rate, illustrating its value of a concept (even if it is mostly useless as an actual practical tool). How? Well, implicit behind the two different perspectives is different view on this ephemeral but crucial thing called the neutral rate. The proponents of easing see current rates as high and restrictive. This then logically means that it is time to cut rates, given that inflation is defeated and labour market is soft. Indeed, it might be becoming too late if we want to avoid labour market softening too much, given the usual lagged effects of monetary policy. The opponents either thing that rates are not restrictive right now, or take the more Socratic view, arguing that it is hard to see any evidence that rates are restrictive, given that the economy keeps humming along and labour market remains quite tight. Which implies there is no urgency to cut.

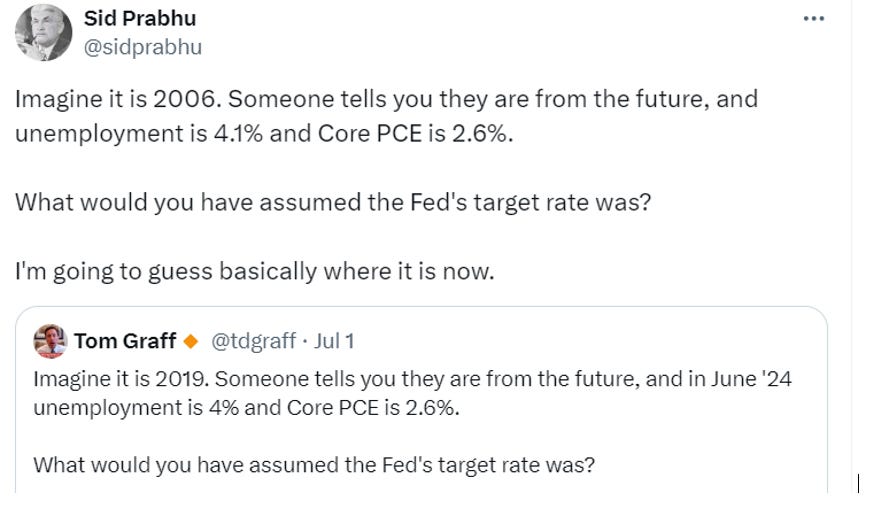

This distinction was neatly captured in this twitter exchange:

Basically, if you use last decade as basis for your estimate of neutral then you have to conclude we are very restrictive. If you look anything else than last decade as your basis, then we aren’t really restrictive.

Last decade, reversed

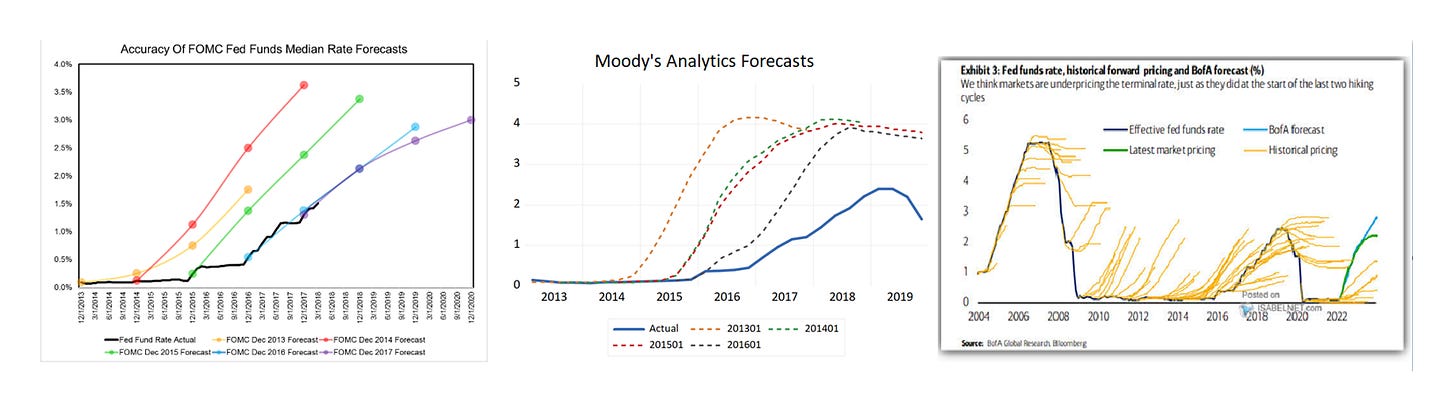

In this sense the current debate is really a mirror image of the conundrum facing monetary policymakers, forecasters and markets during last decade. Back then almost everybody was wrong in expecting rates to increase too soon, too fast and too high:

This pervasive mistake was really about not appreciating at that time that the neutral rate has decreased, the long-term and especially the short-term one. Now the Fed, forecasters and markets might be doing the exact opposite mistake, not appreciating how much did the neutral rate increase from last decade, and especially how high is the short-term neutral rate. Correspondingly, they might be overestimating how restrictive the current stance is and hence the need to cut rates.

But of course, this is just a historical analogy, which might or might not be fitting. It is also entirely possible that rates are rather restrictive, just that the effect of rates on activity is very slow to materialize. I think Skanda Amarnath is the one who reminded me that there distinguishing between “rates are not restrictive, which is why economy continues to grow” and “rates are restrictive, but the transmission to economy is very weak and slow” is pretty much impossible over short horizons of time.

No strong case either way

So my conclusion is that neither side has as strong a case as they claim – at least in the U.S., where we saw strong growth and elevated inflation over last two years and only now are we seeing some moderation in growth. In eurozone I think the case is much stronger, be it because of the growth picture (which was weak), inflation picture (which looks good by now) or the financing picture (where we saw larger increase in effective interest rates and no loan growth).

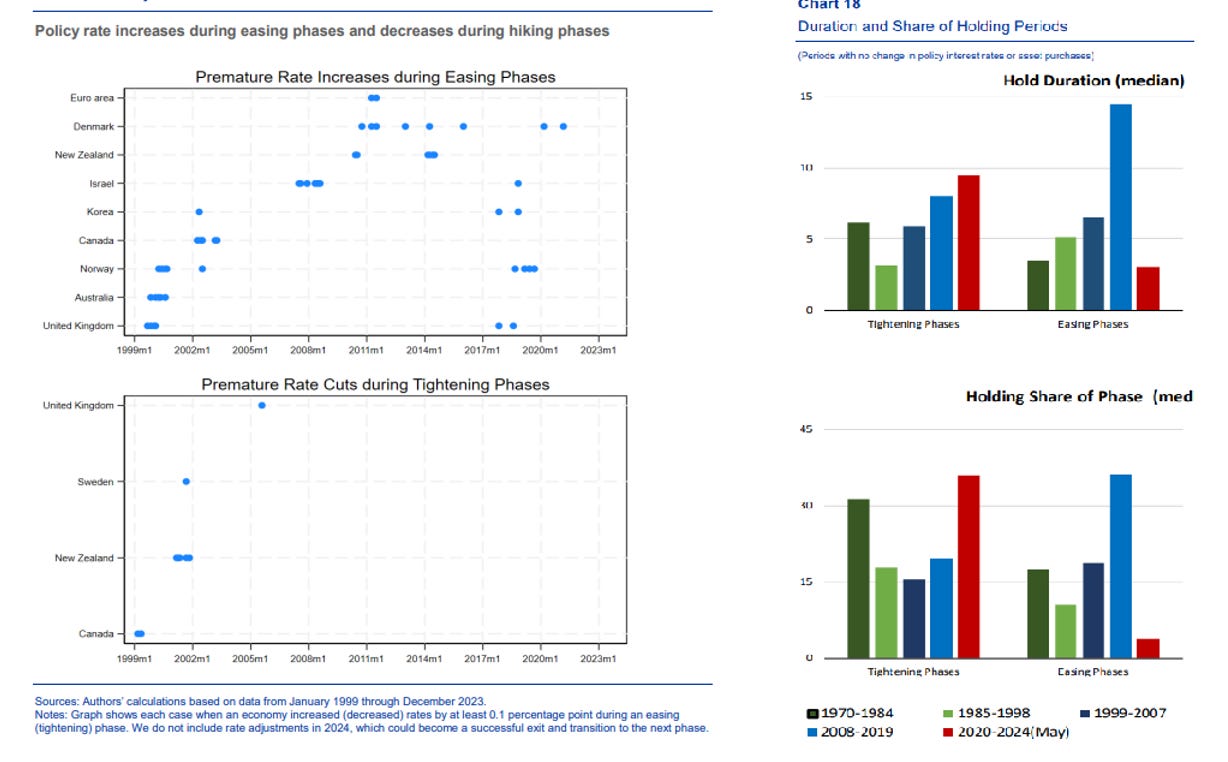

On this topic, I found two charts from recent paper presented at Sintra ECB symposium interesting. First, there is chart which suggests that since onset of inflation targeting central banks almost never do premature easing – which is very interesting observation given that the main lesson one hears about are the dangers of premature easing. Effectively, I think central banks put too much weight on the lessons from 1970s, and if that is any guide, the Fed is likely to wait too long not too short. Aligned with this is the observation that the current hold period following the end of tightening is already the longest for any historical period. Again, this would give some weight to Fed being more likely to wait too long rather than too short. So overall I think the prudent way to approach this – and indeed the way Fed is likely to approach this – is by cutting rates sooner rather than later, but pausing after first few cuts to evaluate the situation.