Was ECB unpredictable in 2022?

Most analysts, including me, were consistently getting the ECB wrong. This was not simply because of surprising economic developments, but to a large degree it reflects shift in behavior by the ECB.

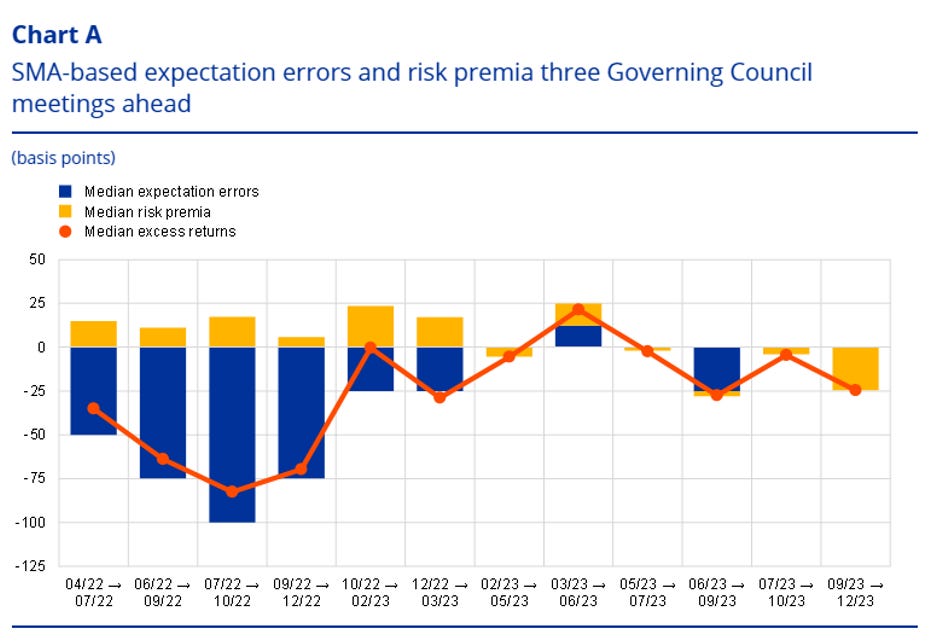

The ECB bulletin has a nice box on topic I was meaning to write about: forecasting ECB policy decisions. The box effectively looks at how did the median forecast in Survey of Monetary Analysts did in terms of forecasting what ECB will do throughout this tightening cycle. The answer? Well, as usual, it depends on forecast horizon. For the upcoming meeting the forecasts were quite precise, but for longer forecasts, specifically 3 meetings ahead, the forecasters did not do so well: there were systematic negative forecast errors, i.e. underprediction of the actual size of increases by the ECB, as shown in picture below (blue bars is difference between median expectation for deposit rate and its actual value, so negative values mean actual was above median expectation).

This is especially true during beginning of the tightening in fall of 2022, but persists throughout – even after the start of hiking in summer the analysts underappreciated the degree to which rates will rise during fall. For example, expectations for December 2022 formed before the September meeting fell significantly short. While expectations for February 2023 meeting from before the October meeting were better, they still did fall a bit short.

The consistent underprediction is only one interesting part of the story, and it is one that is quite easy to explain given consistent upside surprises on inflation. The more interesting and harder to explain part of the story is the magnitudes: the peak underprediction is 100bps, which is gargantuan miss over span of only 3 meetings. Or put it in relative terms, before the July meeting the median expectation for hikes in July, September and October meetings was 100bps, while in reality we got double that amount. Similarly, in beginning of September analysts expected 75bps of hikes over the rest of the year, but we got 150bps, again double the expected amount.

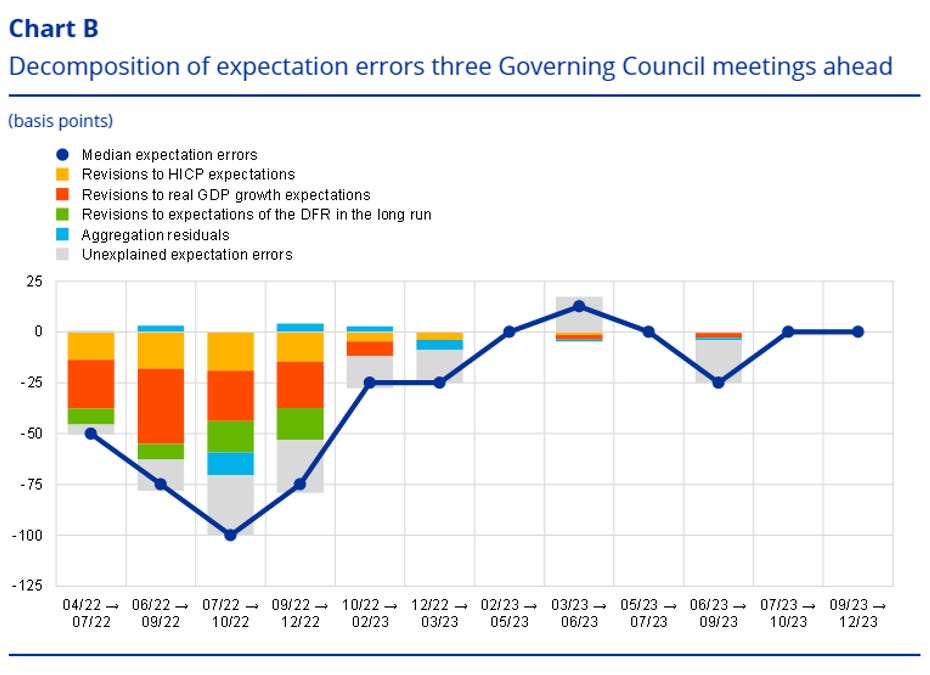

What is behind this? The authors approach this with simple regression analysis, regressing the errors in expectations on revisions to one-year-ahead inflation and growth (together with changes in long-run level of deposit rate). Their takeaway is that significant chunk of this errors can be explained by the revisions to these variables. Hence the errors were not caused by ECB suddenly becoming more hawkish, but rather due to shocks hitting the economy. In the parlor of central bank speak the analysts were not surprised by the reaction function of ECB: If analysts would have the correct forecasts for macroeconomic variables, ECB behavior would to a large degree be predictable.

Here I actually diverge from the authors. To see why, consider starting conceptually from a typical Taylor rule (yes, again), linking interest rates to inflation and output gap (which is mostly equivalent to growth):

interest rate = output + (#) inflation + (#) other variables + disturbance.

In this conceptual framework errors about what the central bank will do can come from the inflation or output being different than expected. Or it can come from central bank behaving differently, which would either show up in different coefficients and , or in shocks. In our case of severe and systematic underprediction we saw above could come from ECB reacting to higher inflation, lower economic growth, or because ECB behaved differently than analysts expected given these values. Of course, it was a combination of all three factors, but the question is the relative role of these factors.

My personal, unquantifiable perspective is that the main driving force for analysts’ errors was the switch to hawkishness of the ECB, with inflation playing important secondary role. At least that was the case for me as one of the analysts.[1] While inflation did surprise on the upside during fall of 2022, and mine inflation outlook did get revised upwards, this is mostly not why I was wrong about ECB. Or take ING analysts as another example, who were very vocal up until the September meeting in their call that ECB will not hike past September, despite inflation which was already approaching double digit values. Similarly, in early 2023 I got the inflation forecast for rest of 2023 right, and yet I initially got the policy forecast wrong.

The reason I (together with others) was repeatedly wrong was because I underestimated to what degree the ECB shifted from forward-looking model-dependent approach to more backward-looking data-dependent approach, and to what degree the consensus shifted towards hawks. (This is not just my perspective, e.g. here).

Why then do the authors find that they can explain the errors with inflation and growth? To see that, notice that largest chunk of the forecast errors is actually explained by growth revisions. This might at first sight sound strange: Wasn’t growth revised downwards? How could lower growth explain ECB raising rates more than expected? Well, the point is that the regression authors run has a negative sign on growth: downward revisions to growth would lead to higher implied expectations for deposit rate and hence smaller errors. The authors put it into context of the supply shock lowering, and there some probably some truth to that. But taking a step back it is hardly a persuasive argument to say that if only would analysts know that growth will be lower in year time they would expect ECB to hike more. And if you take away the effect of growth forecast revisions then most of the errors are indeed unexplained.

What is happening? I think it is combination of few factors. First, I think this is a case of overfitting: they really have observations only for 12 meetings, and some of them do not feature any errors in the median expectation. With such a low number of observations it is not hard to imagine that you will find an effect of some variable. Second, it is a matte of omitted variable bias, with downward growth revisions reflecting news about stagflationary shocks (this is effectively the perspective the authors take). And third, there is also a potential issue of reverse causality: ECB hiking more than expected should lead to lower growth forecasts, explaining the negative correlation between the two. Given these issues, and given that without growth revision effect most of the forecast errors are unexplained, I think the graph actually suggests these are down to unpredictability of ECB.

So overall, I think ECB was unpredictable in fall of 2022. Sure, it usually managed to steer market analysts to correct expectations for the very next meeting – I always got the upcoming meeting call right just before the meeting – but that it not too surprising. More important is the fact that 2-4 meetings ahead market analysts (including me) were being consistently surprised in one direction. And this was not simply about surprising economic developments, suggesting a shift in behavior of the ECB which was missed by most analysts.

[1] Albeit my errors were bit smaller: they were 75bps and 50bps in forecasts made in July and September, respectively.